All the alimentary canal below the stomach. In it, most DIGESTION is carried on, and through its walls all the food material is absorbed into the blood and lymph streams. The length of the intestine in humans is about 8.5–9 metres (28–30 feet), and it takes the form of one continuous tube suspended in loops in the abdominal cavity.

The intestine is divided into small intestine and large intestine. The former extends from the stomach onwards for 6.5 metres (22 feet). It is divided rather arbitrarily into three parts: the duodenum, consisting of the first 25–30 cm (10–12 inches), into which the ducts of the liver and pancreas open; the jejunum, comprising the next 2.4–2.7 metres (8–9 feet); and finally the ileum, which at its lower end opens into the large intestine.

The large intestine is the second part of the tube, and though shorter (about 1.8 metres [6 feet] long) is much wider than the small intestine. It begins in the lower part of the abdomen on the right side. The first part is known as the caecum, and into this opens the appendix vermiformis. The appendix is a small tube, closed at one end and about the thickness of a pencil, anything from 2 to 20 cm (average 9 cm) in length (see APPENDICITIS); the caecum continues into the colon. This is subdivided into: the ascending colon which ascends through the right flank to beneath the liver; the transverse colon which crosses the upper part of the abdomen to the left side; and the descending colon which bends downwards through the left flank into the pelvis where it becomes the sigmoid colon. The last part of the large intestine is known as the rectum, which passes straight down through the back part of the pelvis, to open to the exterior through the anus.

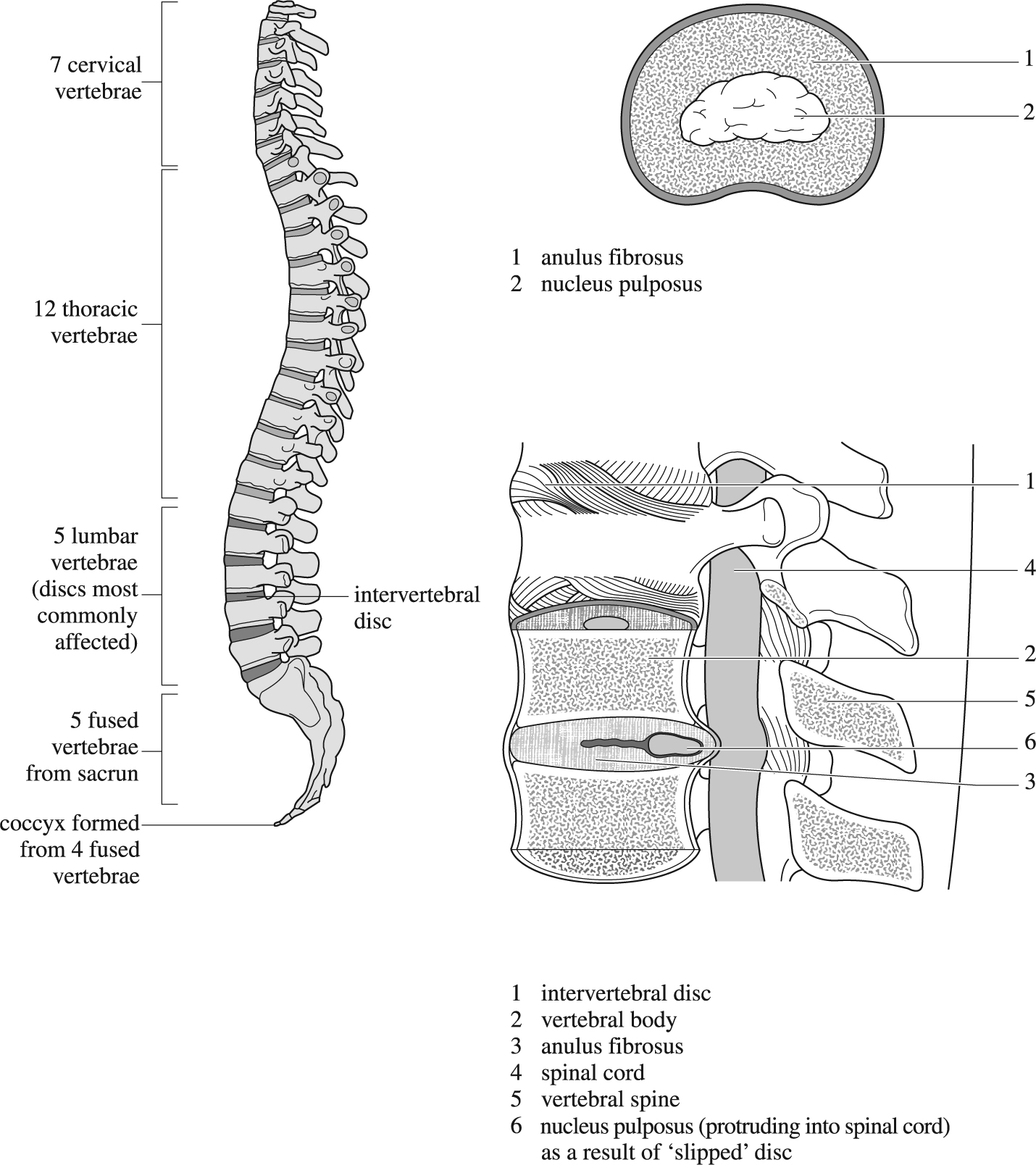

Lateral view of prolapsed intervertebral disc.

The intestine, both small and large, consists of four coats, these vary slightly in structure and arrangement at different points, but are broadly the same throughout the entire length of the bowel. On the inner surface there is a mucous membrane; outside this is a loose submucous coat, in which blood vessels run; next comes a muscular coat in two layers; and finally a tough, thin peritoneal membrane.

The interior of the bowel is completely lined by a single layer of pillar-like cells placed side by side. The surface is increased by countless ridges with deep furrows thickly studded with short hair-like processes called villi. As blood and lymph vessels run up to the end of these villi, the digested food passing slowly down the intestine is brought into close relation with the blood circulation. Between the bases of the villi are little openings, each of which leads into a simple, tubular gland which produces a digestive fluid. In the small and large intestines, many cells are devoted to the production of mucus for lubricating the passage of the food. A large number of minute masses, called lymph follicles, similar in structure to the tonsils are scattered over the inner surface of the intestine. The large intestine is bare both of ridges and of villi.

Loose connective tissue which allows the mucous membrane to play freely over the muscular coat. The blood vessels and lymphatic vessels which absorb the food in the villi pour their contents into a network of large vessels lying in this coat.

The muscle in the small intestine is arranged in two layers, in the outer of which all the fibres run lengthwise with the bowel, whilst in the inner they pass circularly round it.

This forms the outer covering for almost the whole intestine except parts of the duodenum and of the large intestine. It is a tough, fibrous membrane, covered upon its outer surface with a smooth layer of cells.