(Singular: bacterium.) Simple, single-celled, primitive organisms which are widely distributed throughout the world in air, water, soil, plants and animals including humans. Many are beneficial to the environment and other living organisms, but some cause harm to their hosts and can be lethal.

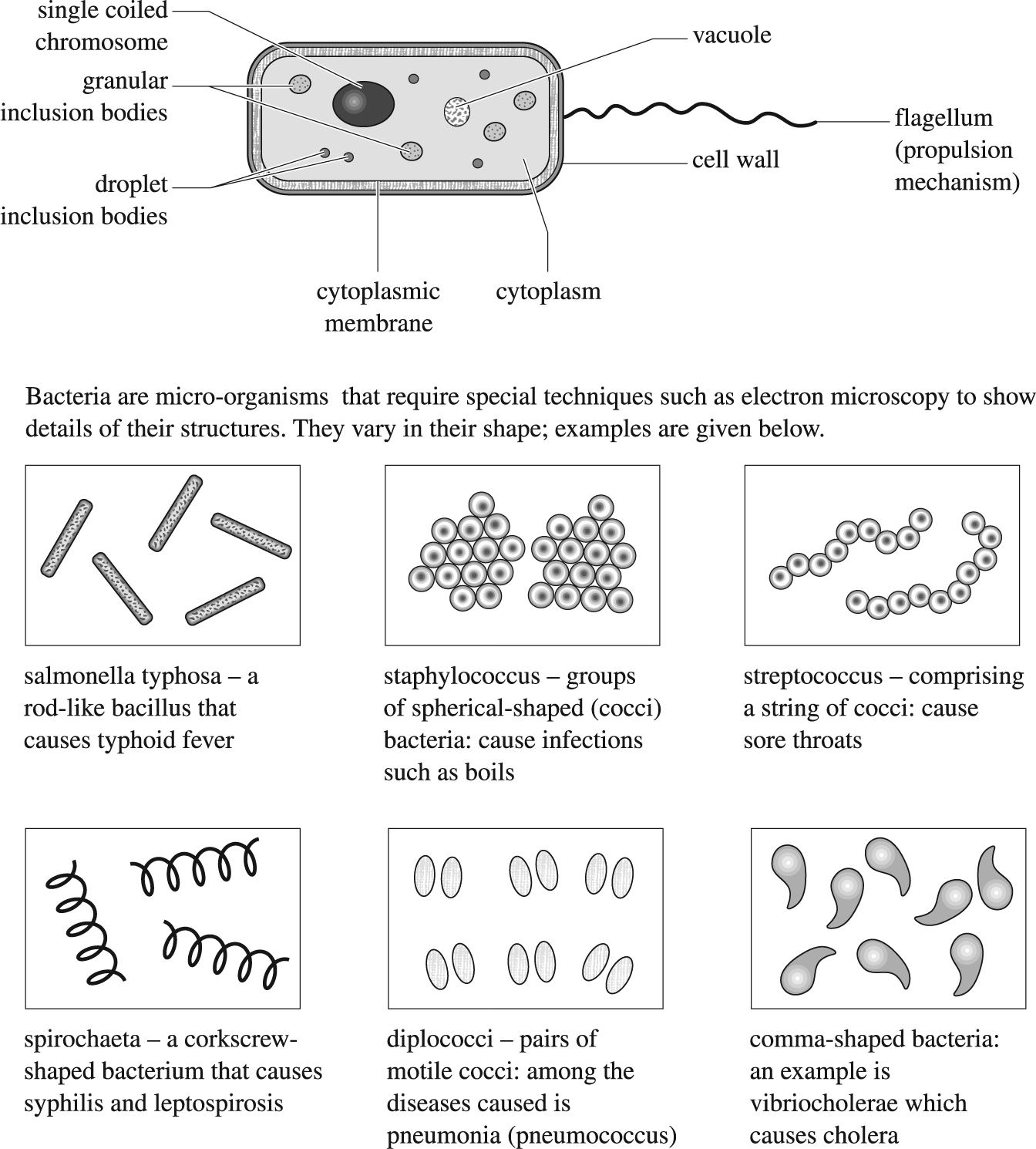

Bacteria are classified according to their shape: BACILLUS (rod-like), coccus (spherical – see COCCI), SPIROCHAETE (corkscrew and spiral-shaped), VIBRIO (comma-shaped), and pleomorphic (variable shapes). Some are mobile, possessing slender hairs (flagellae) on the surfaces. As well as having characteristic shapes, the arrangement of the organisms is significant: some occur in chains (streptococci) and some in pairs (see DIPLOCOCCUS), while a few have a filamentous grouping. The size of bacteria ranges from around 0.2 to 5 micrometres and the smallest (MYCOPLASMA) are roughly the same size as the largest VIRUSES (poxviruses). They are the smallest organisms capable of existing outside their hosts. The longest, rod-shaped, bacilli are slightly smaller than the human ERYTHROCYTE blood cell (7 μm).

Bacterial cells are surrounded by an outer capsule within which lie the cell wall and plasma membrane; cytoplasm fills much of the interior and this contains genetic nucleoid structures with DNA, mesosomes (invaginations of the cell wall) and ribosomes, containing RNA and proteins. (See illustration.)

Reproduction is usually asexual, each cell dividing into two, these two into four, and so on. In favourable conditions reproduction can be very rapid, with one bacterium multiplying to 250,000 within six hours. This means that bacteria can change their characteristics by mutation relatively quickly, and many bacteria, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Staphylococcus aureus, have developed resistance to successive generations of antibiotics produced by man. MRSA (METHICILLIN-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS) is carried by many people and is a serious hazard in hospitals.

Bacteria may live as single organisms or congregate in colonies. In arduous conditions some bacteria can convert to an inert, cystic state, remaining in their resting form until the environment becomes more favourable. Bacteria have recently been discovered in an inert state in ice estimated to have been formed 250 million years ago.

Bacteria were first discovered by Antonj van Leewenhoek in the 17th century, but it was not until the middle of the 19th century that Louis Pasteur, the famous French scientist, identified bacteria as the cause of many diseases. Some act as harmful PATHOGENS as soon as they enter a host; others may have a neutral or benign effect on the host unless the host's natural immune defence system is damaged (see IMMUNOLOGY) so that it becomes vulnerable to any previously well-behaved parasites. Various benign bacteria that permanently live in the human body are called ‘normal flora’ and are found especially in the SKIN, OROPHARYNX, COLON and VAGINA. The body's internal organs are usually sterile, as are the blood and cerebrospinal fluid.

Bacteria are responsible for many human diseases ranging from the relatively minor – for example, a boil or infected finger – to the potentially lethal such as CHOLERA, PLAGUE or TUBERCULOSIS. Infectious bacteria enter the body through broken skin or through its orifices: by nose and mouth into the lungs or intestinal tract; by the URETHRA into the URINARY TRACT and KIDNEY; by the VAGINA into the UTERUS and FALLOPIAN TUBES. Harmful bacteria then cause disease by producing poisonous ENDOTOXINS or EXOTOXINS, and by provoking INFLAMMATION in the tissues – for example ABSCESS or cellulitis. Many, but not all, bacterial infections are communicable – namely, spread from host to host. For example, tuberculosis is spread by airborne droplets, produced by coughing.

(Top) bacterial cell structure (enlarged to about 30,000 times its real size). (Centre and bottom) the varying shapes of different bacteria.

In scientific research and in hospital laboratories, bacteria are cultured in special nutrients. They are then killed, stained with appropriate chemicals and prepared for examination under a MICROSCOPE. Among the staining procedures is one first developed in the late 19th century by Christian Gram, a Danish physician. His GRAM'S STAIN enabled bacteria to be divided into those that it turns blue – gram positive – and those that it turns red – gram negative. This straightforward test, still used today, helps to identify many bacteria and is a guide to which ANTIBIOTICS might be effective: for example, gram-positive bacteria are usually more susceptible to penicillin than gram-negative organisms.

Infections caused by bacteria are commonly treated with antibiotics, which were widely introduced in the 1950s. However, the conflict between science and harmful bacteria remains unresolved, with the overuse and misuse of antibiotics in medicine, veterinary medicine and the animal food industry contributing to the evolution of bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics. Many public health experts consider antibiotic resistance to be a major global threat. (See also MICROBIOLOGY.)