Gastritis is the description for several unrelated diseases of the gastric mucosa.

is an inflammatory reaction of the gastric mucosa to various precipitating factors, ranging from physical and chemical injury to infections. It may represent a reaction to infection by Helicobacter pylori.

Acute and chronic inflammation occurs in response to chemical damage of the gastric mucosa. For example, REFLUX of duodenal contents may predispose to inflammatory acute and chronic gastritis. Similarly, multiple small erosions or single or multiple ulcers have resulted from consumption of chemicals, especially aspirin and NON-STEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DRUGS (NSAIDS).

Acute gastritis may cause anorexia, nausea, upper abdominal pain and, if erosive, haemorrhage. Treatment involves removal of the offending cause.

Accumulation of cells called round cells in the gastric mucosal characterises chronic gastritis. Most patients with chronic gastritis have no symptoms, and treatment of H. pylori infection usually cures the condition.

A few patients with chronic gastritis may develop atrophic gastritis. The incidence increases with age, and more than 50 per cent of people over 50 may have it. A more complete and uniform type of ATROPHY, called ‘gastric atrophy’, characterises a familial disease called PERNICIOUS ANAEMIA. The cause of the latter disease is not known but it may be an autoimmune disorder.

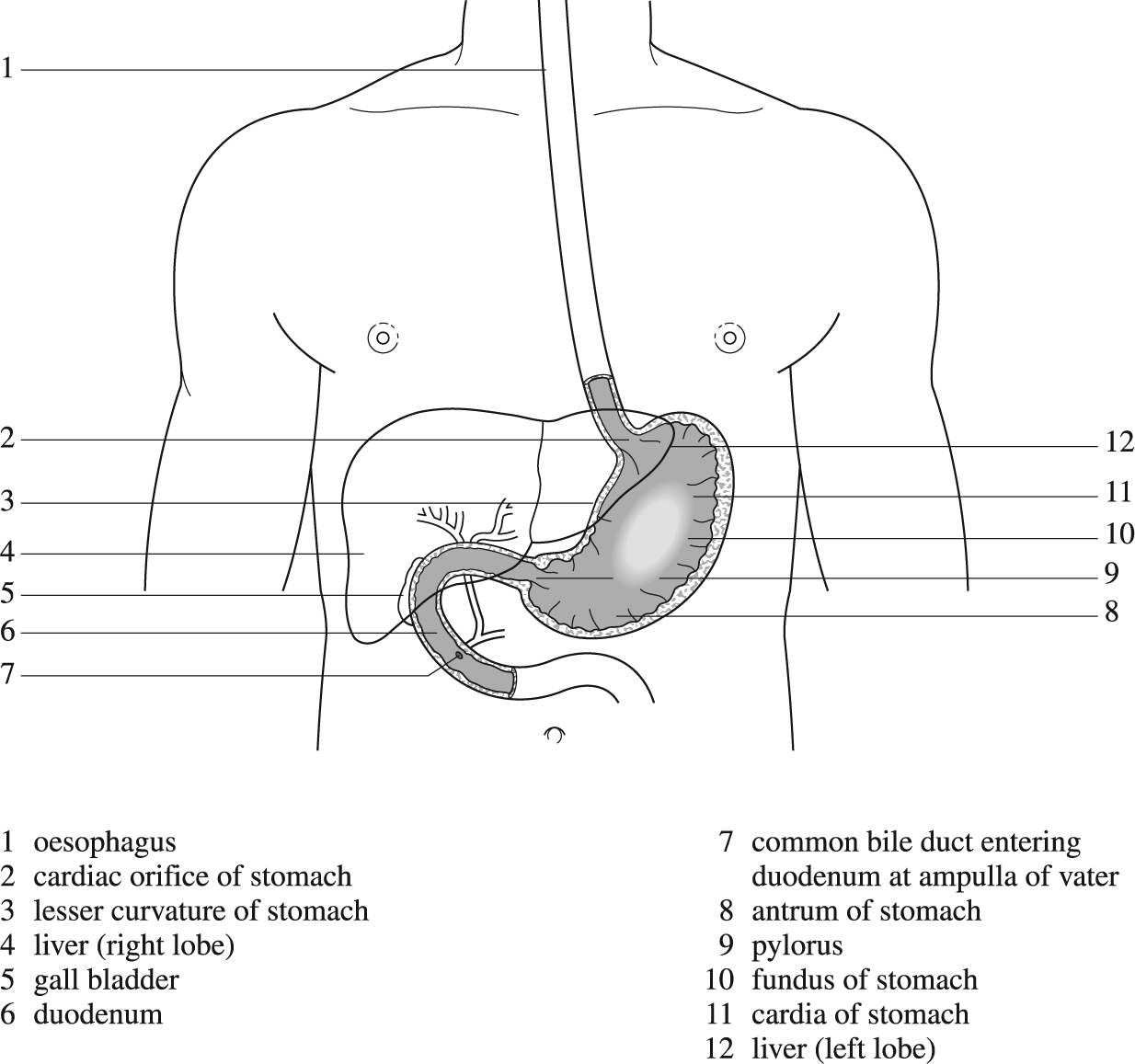

Interior of stomach.

Since atrophy results in loss of acid- and pepsin-secreting cells, gastric secretion is reduced or absent. Patients with pernicious anaemia or severe atrophic gastritis may secrete too little intrinsic factor for absorption of vitamin B12 and so can develop severe neurological disease (subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord).

Acute stress gastritis develops, sometimes within hours, in individuals who have undergone severe physical trauma, BURNS (Curling ulcers), severe SEPSIS or major diseases such as heart attacks, strokes, intracranial trauma or operations (Cushing's ulcers). The disorder presents with multiple superficial erosions or ulcers of the gastric mucosa, with HAEMATEMESIS and MELAENA and sometimes with perforation when the acute ulcers erode through the stomach wall. Treatment involves inhibition of gastric secretion with intravenous infusion of an H2-receptor-antagonist drugs such as RANITIDINE or FAMOTIDINE, so that the gastric contents remain at a near neutral pH. Despite treatment, a few patients continue to bleed and may then require radical gastric surgery.

The two factors most strongly associated with the development of duodenal ulcers – gastric-acid production and gastric infection with H. pylori bacteria – are not nearly as strongly associated with gastric ulcers. The latter occur with increased frequency in individuals who take aspirin or NSAIDs because of inhibition of the enzyme cyclo-oxygenase, which in turn reduces production of repair-promoting PROSTAGLANDINS.

Gastric ulcers usually present with a history of central abdominal pain of up to one year. The pain tends to be associated with loss of appetite and may be aggravated by food, although patients with ‘prepyloric’ ulcers may obtain relief from eating or taking antacid preparations. Patients with gastric ulcers also complain of nausea and vomiting, and lose weight.

The principal complications of gastric ulcer are haemorrhage from arterial erosion, or perforation into the peritoneal cavity resulting in PERITONITIS, abscess or fistula.

Approximately one in two gastric ulcers heal ‘spontaneously’ in 2–3 months; however, up to 80 per cent of the patients relapse within 12 months. Repeated recurrence and rehealing results in scar tissue around the ulcer; this may cause a circumferential narrowing – a condition called ‘hour-glass stomach’.

The diagnosis of gastric ulcer is confirmed by ENDOSCOPY. All patients with gastric ulcers should have multiple biopsies (see BIOPSY) to exclude the presence of malignant cells. Even after healing, gastric ulcers should be endoscopically monitored for a year.

Treatment of gastric ulcers is relatively simple: pain relief is provided with an antacid. The person must stop smoking and should not take NSAIDs. If they test positive for Helicobacter pylori, eradication treatment is given (see DUODENAL ULCER TREATMENT). Otherwise, one of the proton pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole, is given for 4–8 weeks, after which endoscopy is repeated to make sure the ulcer has healed. In patients who relapse, long-term indefinite treatment with an H2 receptor antagonist such as ranitidine may be advised since the ulcers tend to recur. Partial GASTRECTOMY is a rarely performed operation unless the ulcer(s) contain precancerous cells.

Worldwide, this accounts for approximately one in six of all deaths from cancer. There are marked geographical differences in frequency, with a very high incidence in Japan and low incidence in the USA. In the United Kingdom, there is a steady fall in reported cases; around 7,000 people were diagnosed in 2013. Studies have shown that environmental factors, rather than hereditary ones, are mainly responsible for the development of gastric cancer. Diet, including highly salted, pickled and smoked foods, and high concentrations of nitrate in food and drinking water, may well be responsible for the environmental effects.

Most gastric ulcers arise in abnormal gastric mucosa. The three mucosal disorders which especially predispose to gastric cancer include PERNICIOUS ANAEMIA, postgastrectomy mucosa, and atrophic gastritis (see above). Around 90 per cent of gastric cancers have the microscopic appearance of abnormal mucosal cells (and are called ‘adenocarcinomas’). Most of the remainder look like endocrine cells of lymphoid tissue, although tumours with mixed microscopic appearance are common.

Early gastric cancer may be symptomless and, in countries with a high frequency of the disease, is often diagnosed during routine screening of the population. In more advanced cancers, upper abdominal pain, loss of appetite and loss of weight occur. Many present with obstructive symptoms, such as vomiting (when the pylorus is obstructed) or difficulty with swallowing. METASTASIS is obvious in up to two-thirds of patients and its presence precludes surgical cure. The diagnosis is made by endoscopic examination of the stomach and biopsy of abnormal-looking areas of mucosa. Treatment is surgical, often with additional chemotherapy and radiotherapy.